The Service Gap for Individuals with Severe Challenging Behaviors

February 12, 2019

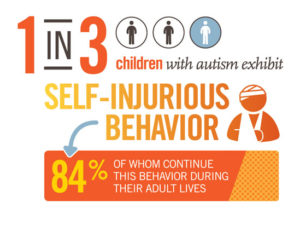

It is well documented in medical literature that many children and adults with autism frequently engage in challenging behaviors such as self-injurious behavior (SIB), aggression, and property destruction. The severity of these challenging behaviors can range from skin-picking and slapping to head-banging, self-biting, punching, and kicking. Research suggests that anywhere from 30% to 70% of individuals with autism with will engage in SIB at some point in their lives.1,2 Possibly more troubling is that left untreated, 84% of these individuals will continue to engage in SIB 20 years later with no significant change in the type or severity of the SIB.3 Pair this with the fact that the rising prevalence rate of autism in New Jersey is the highest in our country, and it’s not hard to conclude that it is a problem that will continue to grow.

Family Impact

In an effort to understand the experiences of families in our state, Autism New Jersey surveyed 200 families whose children engage in challenging behavior. What we found was alarming on many levels. On average, the individual with challenging behavior is:

- A 16-year-old male

- Lives at home with their family

- Is aggressive, non-compliant, self-injurious and/or destructive

- Exhibits these behaviors daily

- Is currently not improving

- Due to these behaviors, the family’s participation in social and other family events is very limited or nonexistent

This is not a manageable situation for any family. It is also important to keep in mind that families with children who exhibit the highest frequency of challenging behavior barely have time in their day to shower and do other basic home chores, let alone find time to complete a survey. All these families want is to keep their child safe while they desperately try to find someone or some place that can effectively treat the challenging behavior.

Assessment and Treatment

Currently, the most well-researched and effective treatment for challenging behavior is Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA).4,5 Over the past four decades, the field of ABA has developed highly effective assessment and treatment procedures that can substantially reduce challenging behavior.

The common ABA assessment and treatment model typically begins with conducting a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA). The purpose of the FBA is to determine the cause/function of the challenging behavior. There are different types of FBA procedures, and the choice of procedure is usually dependent on the setting in which it is being conducted along with the experience and clinical judgment of the Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA).

Once the function(s) of the challenging behavior has been determined, the BCBA will then develop a function-based treatment plan. The function-based treatment plan will include reinforcement and teaching strategies aimed at increasing adaptive behaviors that serve the same purpose as the challenging behavior. As the individual learns that the new adaptive behavior results in the same reinforcement as existing challenging behavior, the frequency of the adaptive behavior should increase while the challenging behavior decreases. Please be aware that this is an extremely over-simplified description of the process and does not include the many nuanced modifications and changes that are typical in an ABA assessment and treatment model.

Even with an effective function-based treatment plan in place, there are several considerations to ensure ongoing success. First, and probably most important, is plan integrity and consistency. Once the plan has been demonstrated to be effective at reducing the challenging behavior, it is key to ensure that caregivers follow the plan as it is written and, if there are multiple caregivers, there is as little variance as possible in how it is being carried out across caregivers. Second, if the individual has a long history of engaging in a specific challenging behavior, changing that behavior may take longer and will require patience and consistency in implementing the plan. Lastly, begin to generalize the plan to different settings. For a plan to be truly effective in the long-term, it must be able to be implemented properly in all the settings that the individual will be in during the day. Caregivers’ abilities to follow the plan, the individual’s history and generalization all present real world challenges to implementing highly specialized behavior plans.

Moving Forward

Today, families often must depend upon existing, unequipped systems, such as psychiatric hospitals, mental health agencies, and emergency rooms to help them keep their child and themselves free from injury. Families are left to their own devices as insufficient and ineffective suggestions are offered. Most often, funding sources attempt to address the challenges only when a situation has reached a full-blown crisis, and in many cases, this could be ten years after the child began engaging in challenging behavior.

With decades of evidence demonstrating that challenging behavior can be successfully treated, it is time that we create systems that provide access to appropriate treatment for those in need. Currently, there are only a handful of programs in the country that have demonstrated long-term success in treating challenging behavior. We must find ways to strengthen existing programs and establish new programs that can effectively reduce challenging behavior and improve the long-term outcomes for these vulnerable children. We must also examine ways to identify and treat children who are at risk for high levels of severe challenging behavior as early as possible. The earlier we can provide effective treatment, the more success we will have in slowing the growth of this escalating problem and keeping children and families safe.

What is Autism New Jersey doing?

- Delivering ongoing technical assistance to CSOC and providers of intensive in-home (IIH) services to strengthen Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) services for children and adolescents with severe challenging behavior

- Sharing families’ stories to shed light on the lesser known sides of autism and let other families know they are not alone

- Providing requested feedback on CSOC’s plan for intensive residential services designed to serve children with severe challenging behavior

- Educating parents about early intervention and evidence-based treatment to reduce or eliminate behavioral challenges and decrease their likelihood

- Working with parents and other organizations to help design innovative housing models for children and adults with severe challenging behavior

- Guiding parents through the process to obtain educational services through their school district and behavioral treatment through the Children’s System of Care and their health coverage

- Providing recommendations to advance DDD’s initiatives to improve statewide capacity so that adults with severe challenging behavior can access timely and effective treatment

Autism New Jersey knows that many families live in vulnerable and desperate situations every day, and we are committed to doing everything we can to systematically improve the quality of life for individuals with autism and severe challenging behavior and their families.

- Bodfish, J. W., Symons, F. J., Parker, D. E., Lewis, M.H. (2000). Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: Comparisons to mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,30(3), 237–243.

- Soke, G. N., Rosenberg, S. A., Hamman, R. F., Fingerlin, T., Robinson, C., Carpenter, L., Giarelli, E., Lee, L.C., Wiggins, L D.., Durkin, M., & DiGuiseppi, C. (2016). Brief report: Prevalence of self-injurious behaviors among children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—A population-based study. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 46(11), 3607.

- Taylor, L., Oliver, C., Murphy, G. (2011). The chronicity of self-injurious behaviour: A long-term follow-up of a total population study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities,24(2), 105–117.

- Asmus, J., Ringdahl, J., Sellers, J., Call, N., Andelman, M., & Wacker, D. (2004). Use of short-term inpatient model to evaluate aberrant behavior: Outcome data summaries from 1996-2001. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37, 283-304.

- Kurtz, P. Fodstad, J., Huete, J., & Hagopian, L. (2013). Caregiver and staff-conducted functional analysis outcomes: A summary of 52 cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46, 1-12.